2023.12.14

5. The End of the Ryukyu Kingdom and Kuninda

Introduction

During the Edo period, the Ryukyu Kingdom utilized China, which was the most powerful autocracy in Asia, as a deterrent to avoid becoming absorbed by the Edo Shogunate, while continuing the tribute trade with China permitted by the shogunate. As the Ryukyu Kingdom became more and more subservient to China, it’s culture also became subject to Chinese influence.

As was mentioned in the previous article, “Kuninda in the Ryukyu Kingdom,” it was the people of Kuninda in the early modern period who conducted the affairs of tribute trade and imperial edicts and were involved in welcoming and disseminating Chinese culture in the Ryukyu Islands.

As a result, many Confucian scholars and politicians emerged from Kuninda, and Kuninda became so influential that the 18th century in Ryukyuan history even came to be called the “Age of Kuninda”. However, after that, Kuninda and the Ryukyu Kingdom came to an end.

So how did the Ryukyu Kingdom and Kuninda come to an end? This article will explain in detail.

Modernization of Japan

The end of the Ryukyu Kingdom and Kuninda coincided with the end of the Edo Shogunate. The reason why is because it was the Edo shogunate that recognized the importance of the Ryukyu Islands and the survival of Kuninda for providing a buffer to as China.

The times changed dramatically as Japan moved out of the Edo period into the Meiji period. It was Japan’s goal to become a modern state with a centralized system of government, and on that basis, it needed to draw clear borders to define its territory.

Until then, the borders of Japan were generally understood to extend only as far as a certain area, but it was now necessary to draw a clear line based on the law of nations (modern international law).

Why, then, did Japan need to draw clear territorial lines in its quest to become a modern nation?

Japan’s rush to modernization

The key question in modernization concerned whether a country was a nation-state or not.

For example, if a problem arose in Japan, it would be necessary to determine whether Japanese law was capable of protecting the rights of its citizens as a nation-state.

Therefore, in the modern era, Japan rushed to establish legislation in the shape of the Constitution of Japan, the Civil Code, and the Commercial Code.

Then the question became, from where to where does the territory of Japan extend, i.e., to what extent does the law apply?

In that case, the status of the Ryukyu Kingdom posed a problem. Since the Ryukyu Kingdom had been subordinate to both Japan and China until then, both countries had a claim to sovereignty and the situation was ambiguous.

With Japan needing to demonstrate clear borders as a territory state, attention fell on the issue of possession regarding the Ryukyu islands.

The Ryukyu situation

The Satsuma Domain imposed a tax on Ryukyu called shinobose and established a government office in Naha called kariya to monitor Ryukyu’s domestic and foreign affairs. While the laws of the shogunate including the prohibition of Christianity and foreign travel to countries other than China were strictly enforced under the isolationist regime, Ryukyu was ruled directly by the Satsuma Domain for 270 years following the Satsuma invasion.

China, on the other hand, ruled indirectly, making Ryukyu a tributary state based on the practices of tributes and imperial edicts. It conducted indirect rule by entrusting the King of Ryukyu, with whom it had established a vassal relationship, with governance of the Ryukyus.

In international law, since the key issue concerns which country has effective control, the Japanese government claimed the Ryukyu Islands as its own territory.

In fact, since indirect rule by way of tribute or imperial edict was not recognized by modern international law, there was no opposition from Western countries, and only China protested vigorously against it.

This placed the Kingdom of Ryukyu in a difficult situation. Until then, it had existed as a dually subordinate nation while trying to achieve a balance of power between Japan and China. If the Ryukyu Kingdom were absorbed and annexed by Japan, it would cease to exist.

The kingdom pleaded in vain with the Japanese government for permission retain its system of dual subordination, however, the Ryukyu Kingdom was placed under the jurisdiction of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the Ryukyu Domain in 1872. Japan then abolished the Ryukyu Domain and forcibly annexed the Ryukyu Islands in 1879.

Kuninda in turmoil

When the Japanese government refused the entreaties of Ryukyu, Ryukyuans sought to revive the Ryukyu Kingdom with the backing of China.

Around the time of the annexation of Ryukyu, many influential samurai families smuggled themselves into China and began a prolonged campaign of petitioning for the restoration of the Kingdom in Fuzhou, Beijing, and Tianjin.

It goes without saying that many of the petitioners were natives of Kuninda, who were skilled in Chinese negotiations and language.

The police authorities in Okinawa Prefecture were on the lookout for people who had smuggled themselves out of the country and engaged in the Ryukyuan revival movement, calling them “deserters to the Qing Dynasty”.

Suicide of Rin Seikō

One of the most symbolic events in the movement in China to petition to government of the Qing Dynasty to restore the Ryukyu Kingdom was the suicide of Rin Seikō. In 1880, negotiations on the Ryukyu issue were being conducted in secret between Japan and China in Beijing.

The content of the proposal was to request an amendment to the Sino-Japanese Friendship and Trade Treaty in exchange for the transfer of the Ryukyu Islands of Miyako and Yaeyama to China, and this was referred to as the “Divided Islands / Expanded Treaty” proposal. The negotiations proceeded to signing in 10 days, and the treaty was ratified within three months.

In order to promote modernization, Japan needed to obtain most favored nation status in China and regain tariff autonomy, etc., while China’s intention was to restore the Ryukyu Kingdom in Miyako and Yaeyama.

However, the restoration of the Ryukyu Kingdom in Miyako and Yaeyama, which were still poor islands at the time, was unrealistic; the King of Ryukyu opposed the idea, and the Ryukyuans petitioning the government of the Qing Dynasty were also firmly opposed.

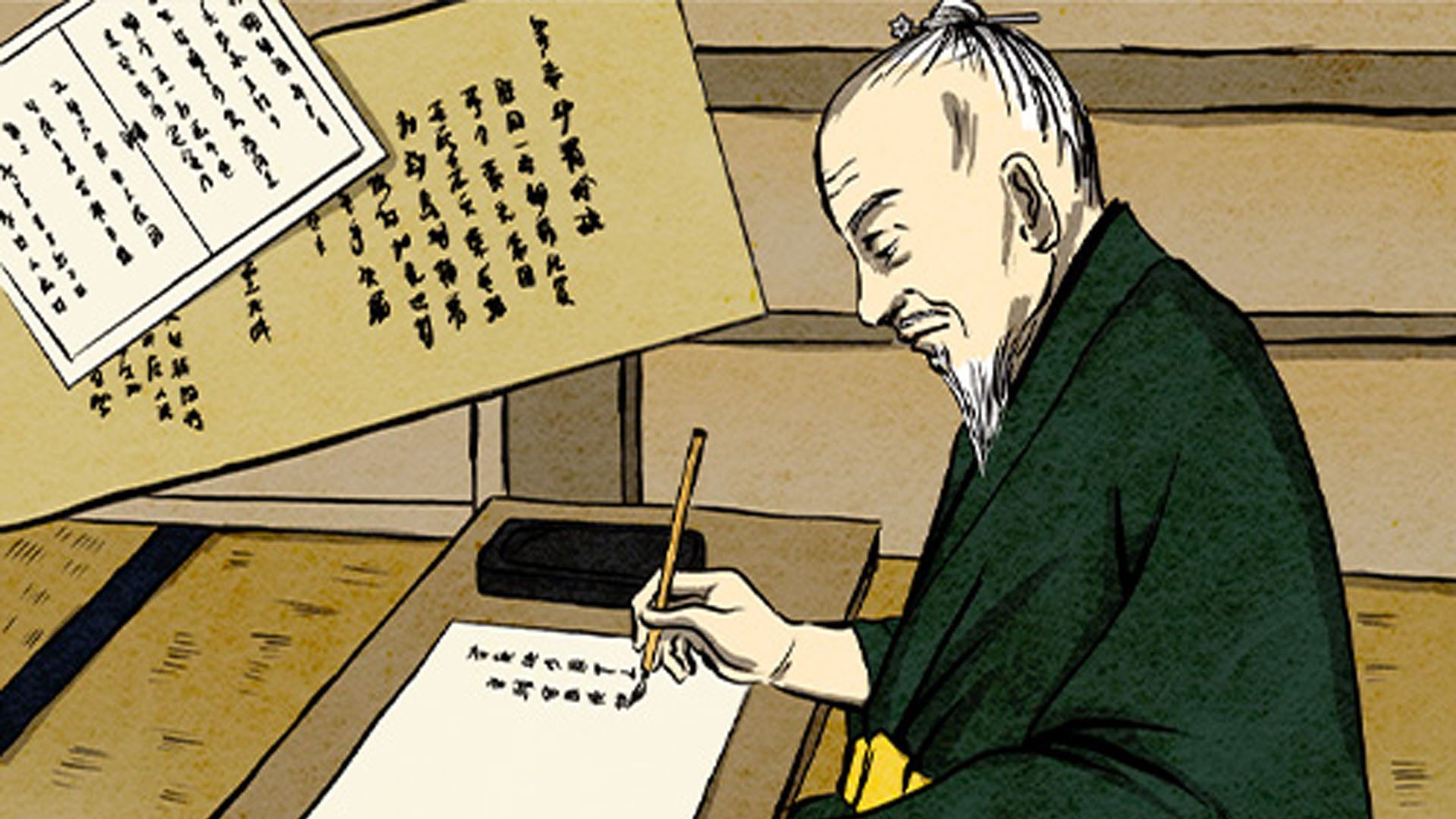

Under such circumstances, Rin Seikō, who was the last official scholar-bureaucrat from Kuninda, submitted a petition two days before the protocol date and committed suicide in protest.

His petitions and poems of resignation to his parents, which expressed his hopes and sorrows regarding the continuation and restoration of the Ryukyu Kingdom, demonstrated the commitment of the people of Kuninda to the movement for the survival of the kingdom at that time.

Amidst the persistent and repeated entreaties of the Ryukyuans petitioning in China, the “Divided Island Revision Plan” became a pending issue, and was ultimately not concluded.

Dissolution of Kuninda

For the Japanese government, which enforced the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands, these petition activities by Ryukyuans viewed as deserters and the presence of Kuninda, which had promoted the penetration of Chinese culture in the Ryukyu Kingdom, were undesirable.

The Japanese government therefore confiscated and nationalized the Kuninda Confucian Mausoleum, the Meirindo, and other facilities that had a strong Chinese flavor in Ryukyuan society, and forced the Kuninda community of professional families toward its dissolution.

In 1894, after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War, the movement to restore Ryukyu to Japan failed, and many of the Ryukyuans who had petitioned in China, including those from Kuninda, returned to Okinawa.

The restoration of the Ryukyu Kingdom through Chinese intervention was never realized, and Kuninda, which emerged during the formative years of the Ryukyu Kingdom, was dismantled along in the Ryukyuan disposition.

Summary

Kuninda emerged during the formative years of the Ryukyu Kingdom and came to play an integral part in shaping the history of the kingdom while being tossed about by the times.

Especially after the invasion by the Satsuma Domain, both the shogunate and Ryukyuans wanted Ryukyu to be positioned as a separate country from Japan, and Kuninda’s importance to the Ryukyu Kingdom can be gathered from the fact that the period when various Chinese culture entered Ryukyu was called the “Age of Kuninda”.

Today, Okinawa has built a unique culture that is a mixture of various cultures from Japan, China, and other East Asian countries, and it is a popular tourist destination in Japan.

Maybe we need to cherish this background and history of Okinawa and think about ways we can make the most of its resources in the modern age.